Since at least 1993, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has argued that central banks should apply a broader definition to prices than the current consumption and production-based measures they currently employ. In 2000, Henry Kaufman, one of the United States’ leading private economists, wrote, “There is no mandate at the present time for any central bank to take into consideration financial asset prices explicitly in the formation of monetary policy. Nevertheless, the bubbling in the American financial market is an untenable situation.”

Arguments in favor of a broader set of price measures include:

• Capital flows that rush into assets are not picked up by conventional measures of inflation. In the past, sudden and signficant capital inflows have had a destabilizing macroeconomic impact and have precipitated a number of financial crises.

• Excessive asset price inflation can touch off a self-reinforcing situation in which an asset bubble develops.

• Asset bubble growth can crowd out saving. With asset prices rising rapidly, the “wealth effect,” can create disincentives for saving. In fact, that is what happened in the run-up of the recent U.S. housing bubble. Personal saving fell from 5.7% of disposable income in the First Quarter of 1995 to -0.7% of disposable income in the Third Quarter of 2005. Moreover, from the First Quarter of 2005 through the First Quarter of 2008, personal saving averaged just over 0.5% of disposable income.

• Reflecting the decline in personal saving was the onset of a “financial accelerator” effect. During the 1990s, personal consumption accounted for 67.5% of real GDP. During the 2000s, personal consumption had increased to 70.6% of real GDP. Since 2005, personal consumption has averaged 71.2% of real GDP. It was the rise in personal consumption that accounted for much of the growth in real GDP that occurred in the 2000-2007 period. During the 1990s, real GDP expanded an average of 3.1% per year. Non-consumption related items of real GDP rose 2.8% per year. In contrast, during the 2000-2007 timeframe, real GDP grew by 2.5% per year, but the non-consumption items increased by just 1.0% per year.

• All bubbles eventually collapse. When equities, commodities, or real estate bubbles pop, they can result in significant macroeconomic damage.

• Real estate bubbles are particularly hazardous given the amount of debt involved. The collapse of real estate bubbles can create financial system fragility, and frequently a financial sector crisis that can take years to heal. Such a crisis can lead to a severe credit crunch. In turn, the increasing grip of a credit crunch can produce a significant and prolonged recession. The ongoing synchronized global recessions provide an illustration of the dangers of a housing bubble.

The major issue involved in pursuing a broader definition of monetary policy concerns whether central banks can detect formative asset bubbles. In 1999, then Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan spoke on that issue. He explained that asset bubbles can lead to economic disruptions, but cautioned that they are very difficult to detect and that preempting asset bubbles would require the central bank’s making a judgment that runs counter to the collective decision making of millions of market participants. He stated:

History tells us that sharp abruptly, most often with little advance notice. These reversals can be self-reinforcing processes that can compress sizable adjustments into a very short time period. Panic market reactions are characterized by dramatic shifts in behavior to minimize short-term losses. Claims on far-distant future values are discounted to insignificance. What is so intriguing is that this type of behavior has characterized human interaction with little appreciable difference over the generations…

We can readily describe this process, but to date, economists have been unable to anticipate sharp reversals in confidence… To anticipate a bubble about to burst requires the forecast of a plunge in the prices of assets previously set by the judgments of millions of investors…

Chairman Greenspan’s concerns aside, history has provided a reasonably good guide that could be used as a starting point for determining when asset valuations are rising to levels that are disconnected from economic fundamentals. By indexing asset prices to growth in nominal GDP, a central bank could be alerted for situations where asset prices begin to sharply diverge from economic growth.

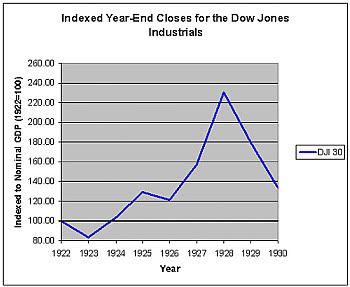

That has been the pattern with past asset bubbles. In the years leading to the 1929 stock market crash, stock prices (as measured by the Dow Jones Industrials) suddenly surged wildly higher relative to nominal economic growth.

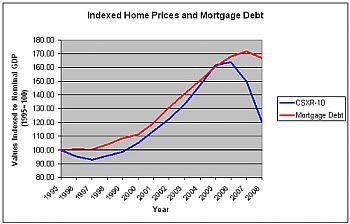

The same pattern reasserted itself with respect to housing prices (as measured by the seasonally-adjusted Case-Shiller 10-city index, as that index goes back prior to 2000) and mortgage debt (home and multifamily residential mortgages).

In the case of the 1929 stock market crash, during 1927 stock valuations rose to 30% or more above cumulative growth in nominal GDP since 1922. By the end of the year, the Dow Jones Industrials’ increase was almost 60% above the level implied by nominal GDP growth.

With respect to the U.S. housing bubble, as indexed to 1995 valuations, mortgage debt reached that threshold in 2002 and housing prices attained that level a year later. In 2003, mortgage debt had grown more than 40% faster than nominal GDP and in 2004 home prices reached that figure.

What is clear in both cases is that asset valuations were rapidly diverging from economic growth. That is a signature of an “upward panic” or euphoria where market psychology increasingly trumps fundamental factors. In both cases, there was a 1½- to 2½-year window of notice that asset bubble formation was underway.

Perhaps tighter monetary policy might have cut short the expansion of the two asset bubbles. Perhaps the economic fallout in the wake of their premature collapse would have been less than ultimately resulted on account of their having been smaller than when they finally collapsed. That is all speculative.

What will be interesting is to see whether China’s central bank actually steers its monetary policy toward a more comprehensive objective that includes reducing the risk of asset price inflation. Even more important, it will be interesting to see whether that monetary policy approach proves effective in the longer-run.

&&

No comments:

Post a Comment