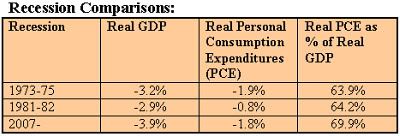

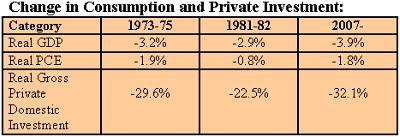

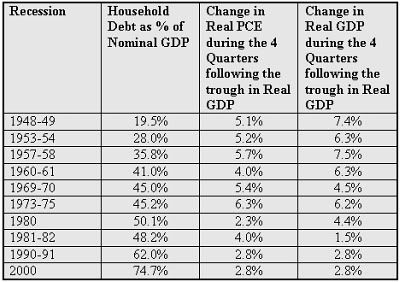

In those earlier recessions, the mean change in real personal consumption expenditures and real GDP for the four quarters following the bottoming of real GDP came to 4.4% and 4.9% respectively. The median figures for real GDP were 4.6% and 5.4% respectively. During the last three recessions, both real personal consumption expenditures and real GDP rebounded notably more slowly.

One popular argument that is often heard is that, in general, the sharper the contraction, the stronger the recovery. A regression analysis of the previous post-World War II recessions suggests a very weak relationship. The coefficient of determination for such an outcome is just 0.180. The mean error using the extent of contraction as the independent variable came to 1.5 percentage points with respect to the actual growth of real GDP in the four quarters following the trough.

A broader set of data that used household debt as a percentage of nominal GDP at the beginning of the recession and growth in real personal consumption expenditures during the four quarters following the trough in real GDP as independent variables fared better. The coefficient of determination came to 0.671. In addition, the mean error was 0.9 percentage points.

Although the data set is small, what the data suggests offers some insight into looking ahead to the robustness of the economic recovery following the bottoming of the economy. In particular, the statistical analysis reveals:

• Higher household debt (as a share of nominal GDP) provides a headwind that impedes the vigor of the first four quarters of an economic recovery.

• The magnitude of the increase in real personal consumption expenditures is positively correlated with the magnitude of increase in real GDP.

In fact, on closer inspection, the data suggest that the magnitude of household debt is a potentially important determinant in how strongly real personal consumption expenditures recover. The coefficient of determination between household debt as a percentage of nominal GDP at the start of the recession and rate at which real personal consumption expenditures rise following the bottoming of the economy is 0.423. In other words, the rate at which real personal consumption expenditures increase following the trough of a recession is, in part, a function of household debt.

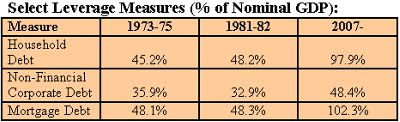

At the start of the current recession, household debt stood at a staggering 97.9% of GDP. 76.3% of that debt was tied up in mortgages. In contrast, during the 2001 recession, household debt came to 74.7% of GDP and 65.2% of that debt was comprised by mortgages. During the 2001 recession, home prices continued to rise. During the current recession, which was sparked by the collapse of a massive housing bubble, U.S. home prices have fallen 32.0%, as measured by the seasonally-adjusted Case-Shiller Index.

In the wake of the collapsed housing bubble, the household sector has been experiencing deleveraging. Household debt has fallen $158.8 billion. In addition, saving as a percentage of disposable income has risen sharply from a quarterly average of 1.5% of disposable income at the beginning of the recession to 5.2% of disposable income in the Second Quarter.

In sum, the household debt burden is another indication that the upcoming economic recovery will likely be shallower than has been the norm during the post-World War II experience. Given the magnitude of household debt, economic growth in the real GDP of 1.5% to 2.5% over the four quarters following the bottom of the recession is probably more likely than the post-World War II median figure of 5.4%.

&&